The Tongue Map is a lie

How does the sense of taste really work?

The '“tongue map” or “taste map”, is a familiar diagram showing distinct areas of the tongue responsible for detecting each of the specific tastes: sweet at the tip, salty and sours at the sides, bitter at the back, and umami in the center.

However, this representation is not accurate.

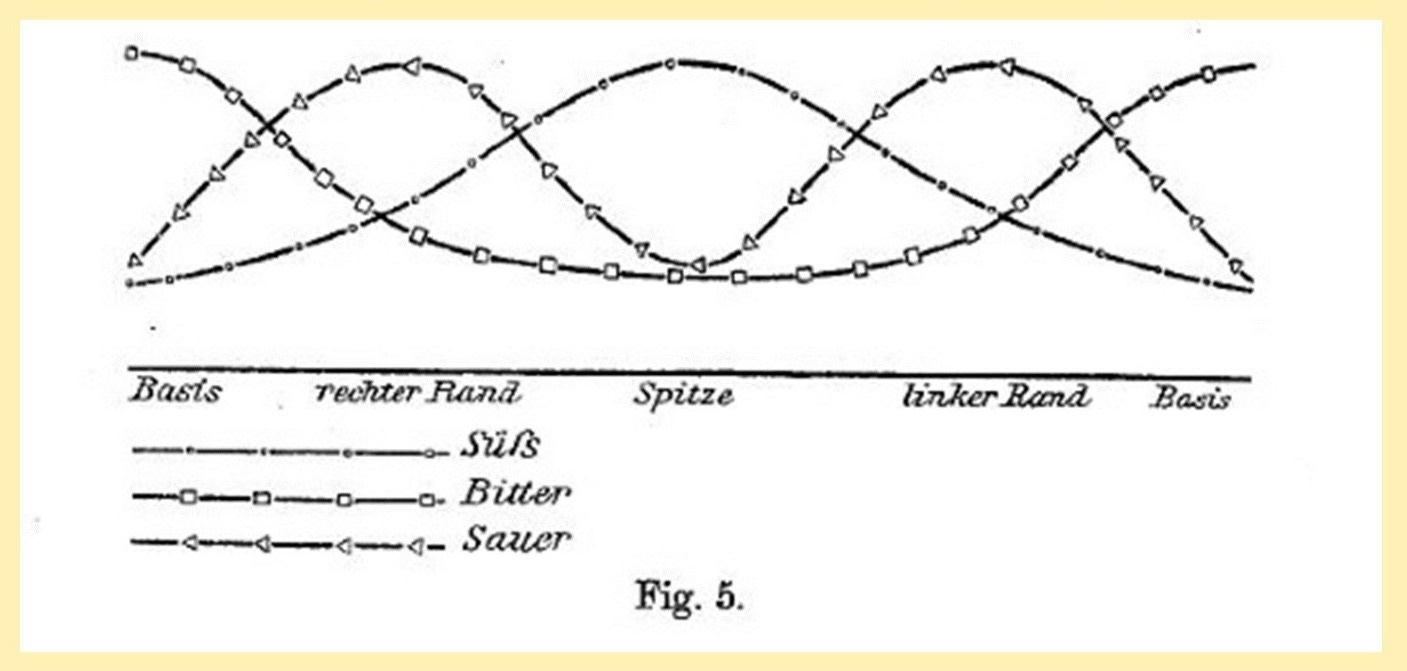

The map originates from a 1901 paper by German scientist David P. Hanig (picture below), who tested sensitivity to basic tastes across the tongue. Hanig found small differences in thresholds (certain regions were slightly more sensitive to particular tastes) but he clearly stated that all parts of the tongue could detect all tastes.

The misunderstanding came later. in 1942, Harvard Psychologist Edwin G. Boring reinterpreted Hanig’s data and published a simplified diagram. Boring’s version exaggerated Hanig’s findings, suggesting that each region of the tongue was solely responsible for one taste. This misrepresentation became the ‘tongue map’ myth still seen today.

It is to be mentioned that neither Hanig or Boring accounted for Umami, which was identified much later (note: umami was first recorded in the early 20th century by Kikunae Ikeda in Japan, but only widely recognized by Western scientists in the 1990s)

Modern research, shows that the taste receptors for sweet, sour, salty, umami and bitter are distributed throughout the tongue and palate. While sensitivity may vary slightly by area, all regions can detect the basic tastes.

How taste detection work

Taste buds are clusters of sensory cells located on the tongue, palate and epiglottis. Each taste bud contains multiple receptors type tuned to detect different classes of molecules.

When we eat or drink, molecules of our food and drink dissolve in saliva and interact with these receptors. Binding triggers chemical signals that travel through the cranial nerves to the gustatory cortex in the brain, where the taste is identified.

Different molecules activate a unique combination of receptors: sugar molecules stimulate sweet-sensitive receptors, while acids in lemon juice trigger sour-sensitive ones. The brain recognizes the pattern of activation to identify the taste.

Because the receptor types are evenly spread, each basic taste can be detected across the tongue rather than in isolated areas.

Sensitivity and Variation

Taste sensitivity varies from person to person. Genetics, age, diet, and health all affect how strongly someone perceives flavour. For instance, genetic variation in TAS2R bitter receptors explain why some people find certain vegetables extremely bitter while others do not (more on this in the future)

The Role of Saliva

Saliva is essential to gustation. The enzymes in our saliva break down the chemical components of what we eat and drink, allowing the resulting molecules to interact with the taste receptors.

The efficiency of this breakdown affects which tastes are detected first. For example, enzymes in saliva (such as amylase) rapidly act on carbohydrates, releasing sugars and helping sweetness appear early. By contrast, bitter compounds tend to resist breakdown and dissolve more slowly (bitter molecules are often bigger and more complex than sweet molecules), so bitterness often develops later on the palate.

In essence, the sequence in which we perceive basic tastes largely depends on how effectively saliva processes each compounds.

Next time you’re drinking a Negroni, try to pay attention to which basic tastes are registered first: sweetness from residual sugar in the liquors will be detected first, followed by the slower emergence of bitterness.

This sequence highlights how taste is a dynamic process, not a static map